Full text (PDF, 787KB)

Madjedi, K., Daya, R. The meaning(s), barriers and facilitators of Anishinaabe health: Implications for culturallysafe health care. UBCMJ. 2016: 7.2 (17-18).

° Corresponding author: kmadjedi@nosm.ca

a Joint MD & MA Student 2019, Northern Ontario School of Medicine, School of Rural and Northern Health, Sudbury, ON

b MSc Student, Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON

* Kian Madjedi and Rukhsaar Daya contributed equally to this article.

Introduction

Aboriginal health is a multi-factorial concept that is influenced by the unique intersection of historical, political, economic, physiological, spiritual, geographic, personal, and community factors.1,2 General definitions of “Aboriginal health” tend to centre around the importance of holism and balance.1,3 While these definitions generally help clarify the basic ontological differences between Aboriginal and Euro-Western notions of health, it is important to recognize and appreciate the tremendous diversity in Aboriginal communities, and with that, a corresponding diversity of ways in which “health” might be understood.4 In developing culturally-safe and respectful approaches to working with Aboriginal peoples, medical and health professional students would be well-served by understanding the ways in which Aboriginal peoples in their region understand and define health and wellbeing in their “own ways and words.”

The following case study examines the ways in which local Anishinaabe (“Ojibwe”) persons in Sudbury, Ontario understand health and wellness.The goal of this research was to determine the various meanings that Anishinaabe people have for the term ‘health’, as well as to identify factors that are perceived by members of the Sudbury community as supportive or challenging to these concepts of health.

Methodology

The researcher engaged with an Anishinaabe elder during the design of the study for guidance on conducting the research in a respectful way. Participants were approached with sema’a (ceremonial tobacco) in recognition of the gifts of knowledge they would be sharing with the researcher. Semi–structured interviews focusing on defining health, and describing factors that support and challenge health, were conducted with sixteen Anishinaabe participants.

Open coding was used to identify themes and a grounded theoretical approach to data analysis and interpretation was employed. Word lists and key words in context tables were used to assist in thematic identification. The study was approved by the Laurentian University Research Ethics Board (REB#20141110). Informed consent from participants was obtained via both written and verbal means.

Results and discussion

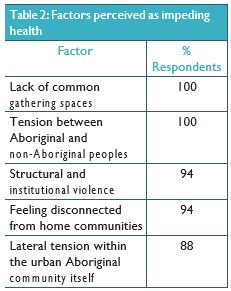

Seven themes emerged in how participants defined health and being healthy: learning and speaking Anishinaabemowin (an Aboriginal language), having mental, emotional, spiritual, and physical balance, living by traditional teachings, being self- determined; (re)connecting with the land; living with respect and reciprocity, and having healthy family relationships (Table 1). Factors that were perceived as impeding health included: the lack of common gathering spaces, tension between Indigenous and non–Indigenous peoples, structural and institutional violence, feeling disconnected from home communities, and lateral tension within the urban Aboriginal

community itself (Table 2).

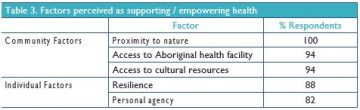

Elements that facilitated Anishinaabe health (see Table 3) were divided into community factors (proximity to nature, access to Aboriginal health facilities, and access to cultural resources) and individual factors (resilience and personal agency).

Learning and revitalizing regional Indigenous languages was seen as a significantly important element in both the “meaning and practice of [their] health.” Connecting youth with elders was frequently referenced as a means to building and sustaining healthy family and community relationships that contribute to overall health. Participants overwhelmingly highlighted the importance of living in a balanced way in their daily life, and explained that “keeping culture and tradition alive” played a key role in being and staying healthy.

Participants frequently defined their health in relation to the belief in and practice of the Anishinaabe Seven Grandfather Teachings of Respect, Honesty, Wisdom, Bravery, Truth, Humility, and Love, and identified these as key teachings in keeping healthy.

Self-determination was seen as a critical factor in being healthy: “being allowed to go about things in our own way, on our own terms is the most important factor for health.” accessing culturally-safe health care was also seen as important in staying healthy, with one participant indicating she could “be healthier when getting care from people who respect [Aboriginal peoples’] way of doing things.”

Several participants explained that living far from their home communities contributed to difficulties in being healthy, and highlighted the importance of “reconnecting with nature and our land” in staying healthy.

“Having places to come together to celebrate our culture and tradition” was identified as an important factor contributing to health, but participants frequently expressed that access to such spaces is notably lacking.

Previous research on Anishinaabe health has typically focused on detailing traditional healing practices, patient experiences, and the integration of Anishinaabe health with biomedicine, rather than on exploring the meanings and experiences of health for Anishinaabe peoples.5 This research highlights the ways in which Anishinaabe peoples define and understand their own health, and demonstrates how a blanket approach to defining Indigenous health might be limited in its applicability to local communities.

The ways in which Anishinaabe peoples define their health highlights both the similarities and differences between concepts of Anishinaabe health, the health ontologies of other Aboriginal peoples and nations, and Euro-Western concepts of health. Anishinaabe definitions of health, and the factors that support and challenge it, clearly present unique relationships informed by local context beyond what might be typically captured in general definitions of Aboriginal health. Considering, exploring, and understanding these nuances can be an important step toward working in culturally-safe ways with Aboriginal communities.

Conclusion

Understanding Aboriginal health, and the factors that support and challenge it,

“in our own words, in our own way,” as expressed by one participant, is critical for health professionals and students seeking to work in respectful and culturally-safe ways with Aboriginal peoples. While similarities do exist in the way Aboriginal peoples across Canada define ‘health and wellness,’ it is important to consider and appreciate the diverse contexts in which Aboriginal communities and peoples define their own health. By understanding how local Aboriginal peoples experience and interpret health in their own ways, we as medical students can deliver culturally- safe healthcare that better supports the aspirations, values, identities, and perspectives of local Aboriginal peoples.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Waldram J, Herring D, Young Aboriginal Health in Canada: Historical, cultural and epidemiological perspectives. Toronto: Uni- versity of Toronto Press; 2006. 28-42 p.

- Reading C, Wein Health inequalities and social determinants of Aboriginal peoples’ health. Prince George: University of Nor th- ern British Columbia. National Collaborat- ing Centre for Aboriginal Health; 2009. 1-21 p.

- National Collaborating Centre for Aborigi- nal Health: An overview of health in Prince George: University of Nor thern Brit- ish Columbia; 2009. 2-7 p.

- Stephens C, Por ter J, Nettleton C, Wills Disappearing, displaced and under valued: A call to action for Indigenous health world- wide. Lancet. 2006;367(9527): 2019-2028.

- Manitowabi D, Shawande The meaning of Anishinaabe health on Manitoulin Island. Pimatiswin: A Journal of Aboriginal and In- digenous community health. 2011;9(2): 441- 58.