by Anya Selleck

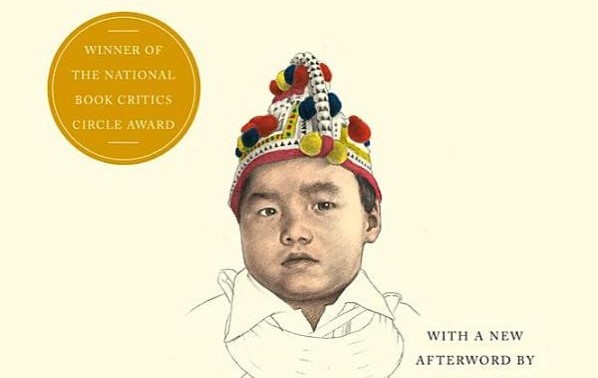

The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down

Book Review

A few years back in university, a friend of mine in medical school gave me a book to read. I didn’t read it. Like so many of my generation, while studying, we place ourselves on a definitive trajectory to our desired goal. With blinders on, we convince ourselves this goal has the utmost virtue, and we get swept away by its potential. Stories like this one almost always get overlooked on our quest for world disease eradication. How could a story of one female child from a remote culture I had never heard of, (the Hmong people from Laos,) situated in a small community in the United States mean anything? Recently, the book found it’s way back to me. I finished it and discovered my initial assumptions those years past were wrong.

‘The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down’ is the literal translation of the Hmong terminology for an epileptic seizure. The journalist Anne Fadiman takes you through the maddeningly frustrating journey of a loving Hmong family and their dedicated western doctors. We watch Lia, the little Hmong girl diagnosed with epilepsy, slowly fade from this world with every seizure. Fadiman brilliantly roasts us over a slow flame by revealing the family’s agony in tandem with the doctor’s feelings of futility. In an age where we love to write about medical incompetence, Fadiman chooses a much more corrosive subject: incompatibility.

Language is inextricably linked to culture, and as a physician, inevitably you will come across a few patients who will bring with them a friend or family member who will be acting as an interpreter. This person will, therefore, be a subjective participant. You as a western doctor are the one with the foreign practice, and even with someone’s belief in their complete complacency, such terms are relative across cultural borders.

The Hmong culture, as Fadiman illustrates, therapeutically centres around Animism. Lia’s own family believed her seizures were caused by her soul leaving her body, which could be returned to her via animal sacrifice. Throughout the book, we see Lia’s Hmong family constantly questioning the doctor’s intention as the doctors uselessly battle against the family’s inability to carry out instructions. How could Lia’s mother take her child’s pulse at home when she doesn’t own a watch or know what a minute is? How could Lia’s family trust the dedication of doctors who angrily throw them out of their child’s hospital room with apparently no reason? (The reason often being that they were frantically trying to administer an IV into a chubby little girl’s arm, with veins impossible to find, as she’s having a seizure.) Then there was the issue with medication. The list of medications Lia was administered or prescribed could span this entire article. Medication is only effective if you take it, and even then, health is not assured. Lia suffers the ill effects of being given medication at the wrong time or sometimes not at all. Fadiman shows us that the effectiveness of western medicine lives and dies depending on execution, whereas, shamanism is dependent on intention. Being a journalist, she maintains a general neutrality throughout her book and tactfully avoids the blame game. No one could ever question the love or dedication Lia’s family and the community had for her. Their intention stretched beyond the normative Hmong way of life, and their co-operation with western medicine was as much as could be expected. No one could question the intention of the many doctors that treated Lia. However, the intention is not their primary job. Theirs was execution and, for whatever reason, that didn’t happen. Western medicine’s inability to solve the staggeringly dangerous problem of proper or consistent outpatient medication intake is one of the greatest medical issues of the 21st century. One could easily argue that once out of the hospital, that this is the patient’s responsibility. However, if execution and timing are truly the modus operandi of western medicine, then those are the primary responsibilities of the physician. It’s a difficult problem, and one devoid of an easy solution. However, I am merely highlighting my opinion of the ethics.

Lia doesn’t die, and I don’t think I’m ruining the book for anyone by saying so. If you are a doctor or a medical student, this is a valuable book to read for all its other reasons. For the attempts of the doctors to get Lia her medication, even going so far as to have her legally taken from her family into foster care with a western family who do THEIR best, and watch everything fall apart anyway. Or for the exquisitely detailed portrait of the Hmong culture Fadiman gives us. She spends a great deal of time with many of them, collecting stories which she comprehensively articulates in the book, not shying away from all the incongruities that the western doctors must face as they pass Lia’s medical file from one set of specialists to another. The crux of this story, however, culminates from the disorientation the western doctor’s experience while juggling a chronic case of epilepsy and an ill-equipped culture’s non-co-operation. Ultimately, they drop the ball. They drop it until nothing works. Her usual drugs become ineffective and she must be given stronger ones. Ones so strong she has to be put under general anaesthesia and a Swan-Ganz catheter invasively threaded into her pulmonary artery. A crash. Septic shock. Bleeding everywhere, as Lia finally develops disseminated intravascular coagulation. A dozen new medications to fight infection. A bronchoscopy, a tracheostomy and a crying, chanting mother who is told her daughter will not wake up, ever. Somewhere along the line, Lia’s brain was deprived of oxygen for too long and she sustained irreversible brain damage.

The inference in the end was, that had Lia been given her anticonvulsants sooner, her outcome would have most certainly been different. As it is, here are the essentials: Had Lia never received western treatment, and her family left to only the devices of her Hmong culture, she would have most likely died in infancy. However, she would have been sent off from this world with ritual, ceremony and almost certain closure for her family. As it is, she did receive that western care and she remained alive, permanently in a vegetative state. Lia would now need 24-hour care for decades, as her family sits with her; on the edge of perception, deaf and mute, between this world and the next.